Owen McNally

Age 11 | Ottawa, Ontario

Last winter, I learned that the Children’s Hospital of Eastern Ontario (CHEO) in Ottawa does not accept donations of used books to share with patients. Despite having no scientific evidence, this rule was created due to concern that books might contain dangerous, or pathogenic, bacteria and make children sick. Instead, to promote literacy they purchase (or take donations of) new books. I decided to explore whether the concern was appropriate by performing an experiment testing whether used books contained more pathogenic bacteria when compared with new books. Thanks to the generous help of multiple staff at the microbiology lab at CHEO (EORLA), I was able to show that while there were slightly more bacteria on used books, none of the bacteria were pathogenic. Based on these results, I concluded that used books are as safe as new ones.

BACKGROUND

Libraries are important as they provide the population with access to books for both entertainment and learning purposes. While beneficial, it is not uncommon for people to visit one or more of their local libraries without finding the book they need or are interested in. This is to be expected given limited physical space and funds to purchase books.

Over the past few years, Little Free Libraries (LFLs) started popping up around Ottawa. These LFLs are a great opportunity to provide communities with a source of book options in addition to bookstores and public libraries. As an avid reader, my personal library has accumulated dozens of books and I wanted to share or donate some of these books as part of a LFL to be placed at CHEO.

However, when I discussed this idea CHEO staff, they were hesitant about installing a LFL over concerns that used books would have dangerous bacteria on them. As an example, they had fears that a child might place a dangerous, potentially antimicrobial-resistant pathogen like vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus or methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus on a book and transmit it to another child, causing disease. Due to this concern, CHEO has largely eliminated sharing used books. To continue promoting reading/literacy, they adopted the expensive practice of purchasing and handing out brand new books to patients.

Interestingly, CHEO is not aware of a time, before or after changing this practice, when a child became sick due to a shared book. Further, when this topic was researched, I found several studies on books in public libraries, with the concern dating back at least a century (McClary, 1974). However, with the exception of one Bible study (Ross and Witzke, 1974), there appears to be a lack of data of microbes on books shared through hospital libraries and private ones.

Recognizing the potential negative impact of these unsubstantiated concerns, I decided to design as study that determines whether used books contain more bacteria compared to new books, and if these bacteria are potentially dangerous. Depending on the findings of this experiment, I hoped CHEO would consider taking used books and allowing me to place a LFL in their waiting room.

PURPOSE

The purpose of this project was to test what percentage of previously used books have dangerous or pathogenic germs on them. I also compared whether used books have more dangerous bacteria than the new books purchased by CHEO and given to patients.

HYPOTHESIS

Four hypotheses were established prior to running the experiments:

Books would commonly have non-pathogenic bacteria (50-75%)

Only a small percentage of books would carry pathogenic bacteria (10-15%)

Only rarely, if at all, would books carry antibiotic-resistant pathogenic bacteria (0-5%)

The difference of bacterium levels between used and new books would be very minimal (<10%).

MATERIALS

For this project, the materials required were SensiCare gloves with Smartguard, 30 E-swab Collection and transport systems for aerobic, anaerobic, and fastidious bacteria. I collected 50 new books from the CHEO library and 50 used books from multiple sources, including my home, school, and books recently donated to CHEO. I used prepared petri dishes containing agar medium and nutrients to grow the bacteria. I collaborated with lab biologists and they helped by using equipment to identify and label the different kinds of bacteria. The dependent variable was bacterial growth (genus, species, how many books and total colonies). After receiving the data, Microsoft Excel was used to process and present the results.

METHODS

The first step was to discuss the project with CHEO (their library, Infection Prevention and Control [IPAC], the Division of Infectious Disease, and the microbiology lab) and receive permission and support for the study. This was felt to be important as it may have implications on hospital policy. As no patients were involved, approval from the Research Ethics Board was not deemed necessary. After collecting both new and used books (the independent variable was the number of books I took from the library, my personal bookshelf, and other sources), I developed the following process to swab the books for bacteria. With gloved hands to prevent contamination, I used 1 swab per book and swiped it in a “Z pattern” across both the front and back to cover a representative surface area. This was a constant variable since I treated each book in the same manner. I then placed the swab into a labelled collection vial and closed the lid. I repeated this method for each book. The Eastern Ontario Regional Laboratory Association (EORLA) generously helped complete this experiment by plating the swabs to grow any bacteria sampled. If bacterial colonies grew, additional tests were performed to determine the genus and species, indicating whether they were pathogenic. If pathogenic bacteria were identified, the plan was to determine antibiotic susceptibly and/or resistance.

OBSERVATION & RESULTS

I was able to quickly acquire 50 new and 50 used books from sources listed in materials. While the original plan was to evaluate for bacteria on all 100 books, it was only possible to sample and obtain results from 30 books total. The main reason for this change in plan was the COVID-19 pandemic, as the infectious disease specialists and EORLA had to reallocate time and resources.

The first observation was that 12 (40%) of the 30 books grew at least one colony of bacteria.

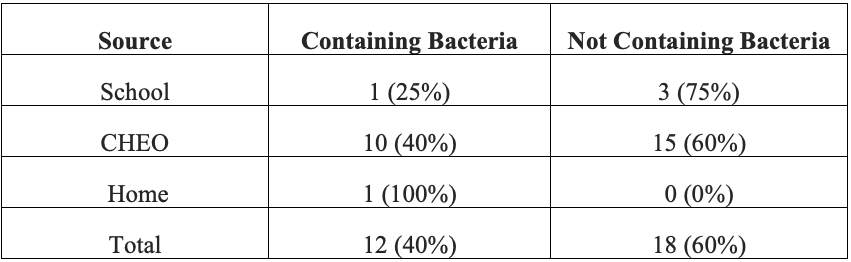

As shown in Table 1, used books were slightly more likely to grow bacteria (47%) when compared with a new book (33%). Table 2 presents the bacterial results (growth or no growth) by book source. Bacteria were identified on books from all three sources (school, CHEO and home library). One somewhat irrelevant but interesting note is that a fungus grew on one of the books. Unfortunately, the lab biologists were not able to confirm whether this fungus was harmful or not.

While 12 books grew some form of bacteria, these books had 37 different colonies of bacteria in total. Speciation of the colonies identified that none were potentially pathogenic (and therefore none were antibiotic-resistant pathogens, see Table 3). As shown in Table 4, there were 10 different bacteria types identified.

Table 1: Number of books with measurable bacteria

Table 2: Number of bacteria on books per book source.

Table 3: Number identified of each type of bacteria: non-pathogenic, pathogenic and pathogenic antibiotic resistant.

Table 4: Which bacteria were found, how many different books they were found on, and their total number of colonies found across all the books.

DISCUSSION

This project provides information on the important question of whether used books carry more bacteria than new books. This study was also designed to take the additional steps of identifying whether the bacteria were pathogenic, and if so, if they were resistant to antibiotics. Findings are relevant for establishments that promote literacy and care for populations at risk of illness – such as hospitals.

The first result from my study is that 40% of books I swabbed grew at least one type of bacteria. While this represents a meaningful percentage of the books, it was less than the 50 to 75% range established in the hypothesis. Although my hypothesis was incorrect, it was wrong in a favourable direction. When evaluated by book type, I observed that used books had a higher percentage with one or more bacterial colonies when compared to new books (47% vs 33%). However, this difference was minimal, and it is interesting to note how common it was to find microbes on new books.

In addition to evaluating for the presence of bacteria, I sought to determine the percentage that were potentially pathogenic (dangerous) or non-pathogenic (commensal). While in my hypothesis I predicted 10 to 15% of the books would have a potentially pathogenic bacteria, none were identified. The results are consistent with a hospital study also reporting that only a small number of Bibles found in hospital rooms had a pathogenic bacterium (2%), concluding it was not a major problem (Ross and Witzke, 2017). As no pathogenic bacteria were identified in my study, it was not possible to evaluate for differences between book types, or to look for antibiotic resistance. While no pathogenic bacteria were identified in my results, others performed studies on books have reported different findings. For example, a study at the University of the Cesar Lattes library evaluated 24 publications over a three-month period, identifying 9 bacteria isolates with multiple being potentially pathogenic (Pio de Sousa, 2020). One additional interesting observation from my study of unknown significance was the identification of a filamentous fungus. Unfortunately, it was not possible to determine if it was potentially pathogenic. Other library studies have identified fungus (Leite et al., 2012; Karbowska-Berent et al., 2011) For example, Leite and colleagues analyzed 84 dust samples from archived books and identified cryptococcus, which they hypothesized to be introduced by pigeon droppings (Leite et al., 2012). Taken together, these findings suggest the study setting and origin of the book may be an important factor in microbe levels and type.

LIMITATIONS

The main limitation of this study was the sample size. Because of the pandemic, neither the disease specialists or EORLA lab biologists had the time or resources necessary to examine all 100 books. Having a larger sample size would have more precisely shown how common it is for pathogenic bacteria to appear on new or used books. An additional limitation was the lack of variety in the sources of books used for the study. The quality of books could be better or worse in different sections of Ottawa and other cities. Finally, I only evaluated for bacteria, and did not test for viruses, another common source of infections. If viruses were found in books after the LFL was set up, it would be consequential. However, this may be less of a concern as viruses are known to quickly break down when outside of a human host.

FUTURE STEPS

As future steps, I may test other items commonly used at children’s hospitals for entertainment or distraction during uncomfortable procedures, including iPads, gaming consoles, and toys. If harmful bacteria or viruses are found on these items, the study should also search for safe and inexpensive solutions for decontamination, including chemical, ultraviolet radiation, and heat.

CONCLUSION

I believe that my results suggest the entertainment and literacy benefits of used books outweigh the small infection risks and will help support establishments that want to share books. As an example, the results were considered by CHEO and contributed to their decision to support the placement of my LFL in the main waiting room. By publishing in the Canadian Science Fair Journal, I hope that others concerned about pathogenic bacteria can see my results and be less concerned about using used books in their bookshelves or libraries.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Thank you to the CHEO staff who helped make my science fair project possible, including Drs Margaret Sampson (CHEO librarian), Nisha Thampi (Infection Prevent and Control) and Bob Slinger (Microbiology). Special thanks to Dr. Maude Paquette (Infectious Disease Fellow) who performed sample analysis in the microbiology lab at Eastern Ontario Laboratory Association (EORLA). I also appreciate EOARLA for providing access to their facilities and equipment at no cost.

REFERENCES

Ross, B., & Witzke, O. (2017). Bibles as a possible source of pathogens in hospitals? A pilot observation. Infection, 45(3), 323-325. https://doi.org/10.1007/s15010-017-0984-5

Karbowska-Berenta, J., Górnyb R.L., Strzelczyk A.B., & Wlazło A. (2011). Airborne and dust borne microorganisms in selected Polish libraries and archives. Building and Environment 46(10), 1872-1879. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.buildenv.2011.03.007

Leite, D. P., Jr, Yamamoto, A. C., Amadio, J. V., Martins, E. R., do Santos, F. A., Simões, S., & Hahn, R. C. (2012). Trichocomaceae: biodiversity of Aspergillus spp and Penicillium spp residing in libraries. Journal of Infection in Developing Countries, 6(10), 734–743. https://doi.org/10.3855/jidc.2080.

de Sousa, L.P. (2020). Diversity and dynamics of the bacterial population resident in books from a public library. Archives of microbiology, 202(7), 1663-1668. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00203-020-01880-5

McClary, A. (1985). Beware the deadly books: a forgotten episode in library history. Journal of Library History (Tallahassee, Fla: 1974), 20(4), 427-433.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Owen McNally

Owen is a grade 7 student that grew up in Ottawa and attends Westboro Academy. He has contributed to his school’s science fair every year since kindergarten and placed in the top 3 multiple times. Owen has always had a keen interest in math and science and has participated in the Spirit of Math School program for 6 years. He plays competitive soccer and hockey and likes to read in his spare time. Owen is always questioning the world around him and likes to understand the reasoning behind rules and policies, hence the idea behind this project.