Wishva Kosgoda

Age 14 | Saanich, British Columbia

Many emigrants from countries in the Eastern world experience significant cultural and lifestyle changes upon arrival in Western nations. These experiences are not just limited to delicious foods, but also other lifestyle practices such as toilet hygiene. One particular change of interest is an often overlooked component of personal hygiene: Eastern countries use water for anal cleansing after defecation, while Western countries typically use dry toilet paper. When the world citizens are called upon to lead a life with minimum impact to the world’s climate, washing after defecation could be the most eco-friendly to the world due to a reduction in paper consumption. To this end, it is also tempting to investigate the level of hygiene one could achieve from wiping compared to washing.

INTRODUCTION

Colorectal cancer (CLC), is an Environmental disease driven by cultural, social, and lifestyle practices (Fatima A., et. al, (2009), Pfadenhauer L. M. and Rehfuess E. (2015), Young S. W. et. al (2015), Forman et.al (2014), Ferlay et. al (2014), Marmot et. al. (2007), Mishra et al, (1996)). There are noticeable geographic differences in the global distribution of CLC (Stewart B.W. and Wild C. P. (2014), Parkin et. al (1999), Forman et.al (2014)), however, it is mainly believed as a disease of Western Cultures. Viruses, bacteria, and parasites are living organisms found all around us and can cause a wide variety of illnesses including cancer (World Watch Magazine, July/August 2007). Given this, and the marked differences evident in toilet hygiene practices of the Western and the Eastern world (Wipe vs Wash), it would be interesting to investigate possible relationships between CLC and toilet hygiene practices between the Western and the Eastern world.

There were several related aims investigated in this study. The first aim was to investigate the level of hygiene achieved from water-based cleaning (Wash) and toilet paper (Wipe) where the former is considered as the most environmentally friendly approach. In this, it was hypothesized that the Eastern practice of washing would yield decreased bacterial growth. The next aim was to investigate how immigration from East to West influences lifestyle changes. Variables would include toilet hygiene practices as well as food habits. Here, it was hypothesized that immigration would significantly change lifestyles compared to the country of origin. The final section of the study attempted to identify whether toilet hygiene could be a potential missing piece in the colorectal cancer epidemiological puzzle. The first aim was investigated with an experiment, the second aim was investigated via a school survey, and the final aim was investigated through an analysis of academic literature.

EXPERIMENT PROCEDURES

The first experiment included swabbing tests, where three Test Cases (Test Case 1: female teenager, Test Case 2: female adult and Test Case 3: male adult) collected swab samples on to an agar plate from their anal area after the excretion process. First, a control with no cleansing (CEXP) was spread on one side of the growth plate. Then, on the other side of the plate, samples from three cleansing techniques were spread: toilet paper (TP), water (W), and water and soap (WS). Essentially, a single plate contained the amount of bacteria before cleansing (CEXP) on one side and the other side contained bacteria from one of the three after cleansing methods (TP, W and WS). Having the control (CEXP) on the same plate ensured consistent environmental conditions and incubation time for the control and the test case.

Participants were provided with detailed instructions and materials such as sterilized swabs, latex gloves, agar plates, and Parafilm to complete this process. The samples were delivered to the University of Victoria (UVic) biochemistry laboratory for controlled incubation at 37°C for 24 hours. After incubation, the agar plates were placed in a fridge to stop bacterial growth. Pictures of the agar plates with bacterial growth were taken for a visual analysis. Each sample was compared to its control on the same plate, ensuring consistent environmental conditions and incubation time for the control and the test case. The agar plates were photographed and safely discarded under the supervision of staff at the UVic laboratory. The above experiment was repeated on two separate samples collected from the participants to verify the consistency of the results. Table 1 below summaries the experimental procedure. This experiment was approved by the Vancouver Island Regional Science Fair (VIRSF) Ethics committee.

Table 1. Experimental setup.

Figure 1. Agar plate setup of the experiment (top). Working in a sterilized environment at the University of Victoria laboratory under the guidance of UVic staff (bottom).

The second section of the study involved an anonymous online survey to obtain statistics on how immigration from East to West could impact food habits and toilet hygiene practices. The purpose was to better understand the extent to which both food habits and toilet hygiene practices change due to emigration. The survey was presented to the Arbutus Global Middle School (AGMS) students under the supervision of the principal Mr. Rob Parker, where the students were asked to participate at their discretion. The students at this school were chosen to participate in this survey due to the large diversity of ethnicities. In total 60-students participated in the survey which represents 15% of the total students.

Due to space limitations, only one key finding from the literature review, that supports my hypothesis that toilet hygiene could indeed be a missing variable in CLC Epidemiologic studies is presented. This section of the study focuses on analyzing data from published sources and comparing data that could establish possible evidence of toilet hygiene being a missing variable in CLC Epidemiologic studies.

RESULTS

Bacterial growth experiments for each participant showed clear variations in growth patterns between cleansing methods under different test cases (C, TP, W, WS). Figure 2 shows test results for the two trials performed, where toilet paper samples had more bacterial growth than the other water-based methods of cleaning.

Figure 2. Experimental results trial 1 (round 1, left) and Trial 2 (round 2, right).

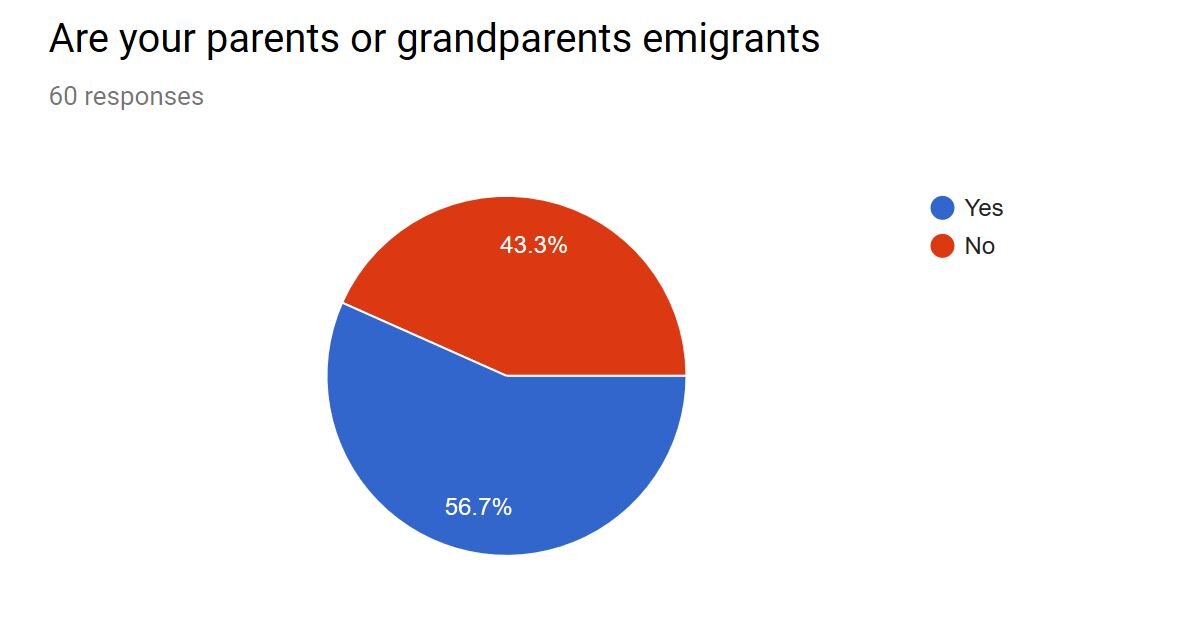

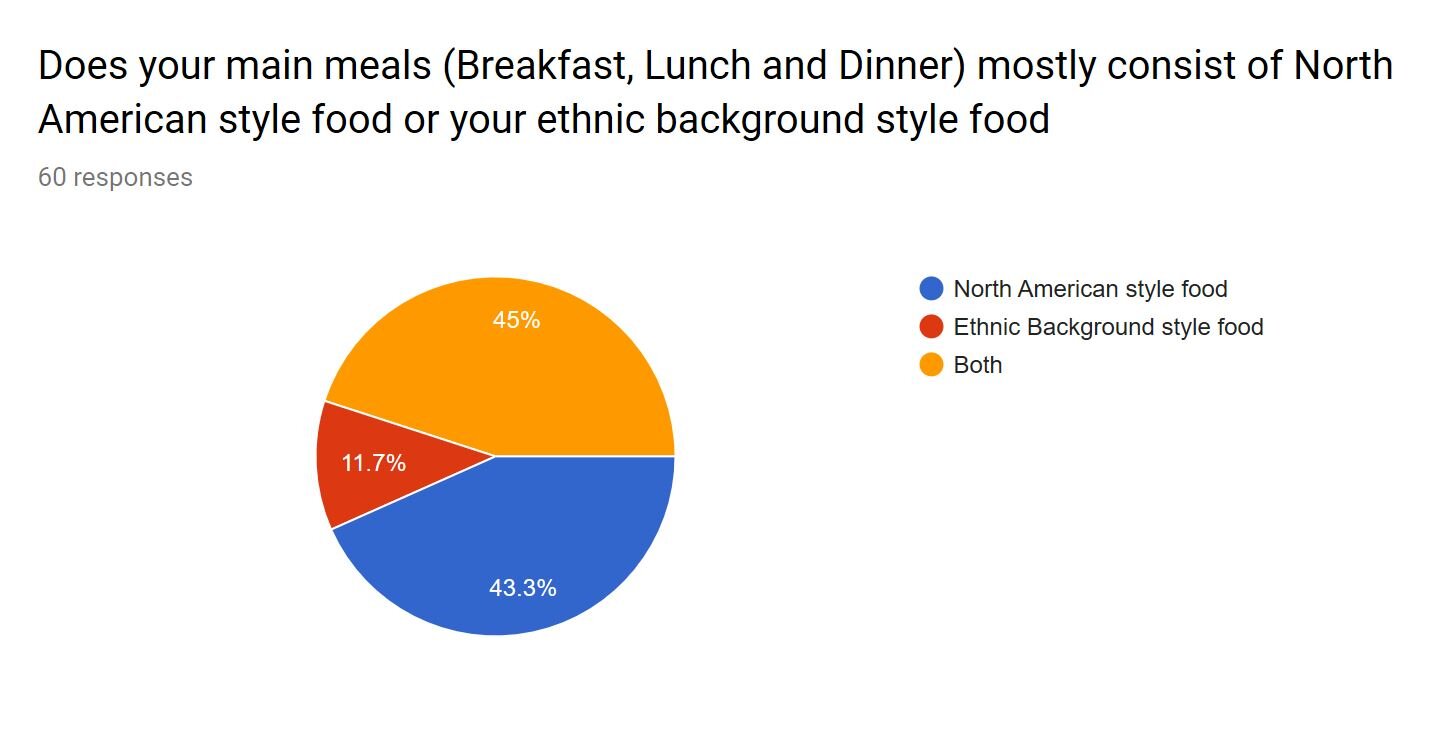

In assessing aim two, students approached by the school-based survey indicates the following results (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Graphs depicting the school-based survey response presented as percentage of total participants (%).

The majority of students (57%) had parents or grandparents who emigrated (Figure 3B). 78% used toilet paper for hygiene (Figure 3C), and 43% of individuals said their bathroom hygiene had not changed from their country of origin (Figure 3D). 66% of the students had parents or grandparents who used toilet paper for anal cleansing (Figure 3E). 45% of participants said their eating habits/styles included a mix of ethnic background and North American style food (Figure 3F). Individual results showed that Emigrants from East tends to eat ethnic food more. Finally, results from the liteature review are presented in Figure 4.

Figure 4. World CLC incidences, food and meat consumption and cost of toilet paper.

In Figure 4, the top two panels show male and female world CLC incidences (age standardized) based on GLOBOCAN2000, the two middle panels show the Global Distribution of Meat Consumption and Food (energy) consumption, and the bottom panelshows a map of toilet paper cost per capita for 48 countries in the world taken in 2017. The latter was generated based on consumer statistics obtained from “Statista”(https://www.statista.com/), and the results were mapped using a free online mapping tool (http://mapinseconds.com/). Unfortunately, the “Statista” portal only releases consumer statistics for 48 countries free of charge; as such, many parts of the world are marked as “No Data” in this map. However even with limited toilet paper usage data, clear relationship between countries with higher CLC incidences and higher toilet paper usage emerged. As can be seen, meat and food consumption maps, toilet paper usage map and the CLC maps are closely related. If high meat consumption is considered as contributing to CLC, then based on the world distribution patterns, toilet hygiene practices should also be considered as contributing.

DISCUSSION

Epidemiological studies suggest a significant CLC burden in the Western world and a lower burden in the East. There are marked differences in eating habits and toilet hygiene practices of these two groups of countries. This research is an attempt to shed light on a potential relationship between toilet hygiene practices and CLC using a mixture of real data, extrapolations from limited samples and informed guesses. So far, CLC related epidemiologic studies have not considered toilet hygiene practices as a variable. Through literature review on toilet hygiene practices, toilet paper usage statistics and trends around the world, this study suggests that there could be a notable correlation between CLC and toilet hygiene. Further, the experimental component qualitatively identifies impacts of various sanitation interventions on hygiene. This is an aspect of hygiene that has rarely been studied.

The results of the first experiment that included swabbing tests, indicated overall, the water and antibacterial soft soap producing the best cleansing results. These results suggest that water based anal cleansing methods are better than toilet paper. Even ecologically, wash method is better for the environment. The second aim of the study, that was approached by the school based survey indicated that due to westernization (i.e. emigration to the west) not just food habits but also considerable changes to toilet hygiene habits from the country of origin takes place. However, the impact of these noticeable changes in toilet hygiene practices from washing to wiping due to emigration is not accounted in most CLC Epidemiological studies as a reason for the increase in CLC incidences in emigrants when emigration occurs from East (i.e. Japan, India) to West (i.e. USA) (Mishra et al, (1996), Stewart B.W. and Wild C. P. (2014), Ferlay et al (2014)) . To this end, the results of this survey sheds light on the value of adding the impact of changes to toilet hygiene practices from westernization into CLC Epidemiologic studies moving forward.

Finally, as per the literature review, even with limited toilet paper usage data, clear relationship between countries with higher CLC incidences and higher toilet paper usage emerged. As can be seen, meat and food consumption maps, toilet paper usage map and the CLC maps are closely related. If high meat consumption is considered as contributing to CLC, then based on the world distribution patterns, toilet hygiene practices should also be considered as contributing. As such, researchers should consider including toilet hygiene practices as a variable in future CLC Epidemiologic studies.

CONCLUSION

This study suggests use of water for cleansing as a method to improve peri-anal hygiene. Relating to this, and the strong emerging patterns between the world distribution of CLC incidences and toilet paper usage, it is recommended that toilet hygiene practices be considered as a variable in future CLC epidemiologic studies. This step will provide insight into one of many lifestyle changes that could reduce the CLC burden from the world. In addition, moving from Wipe to Wash will shift the world towards eco-friendlier living.

Hopefully the results of this study would motivate researchers to connect toilet hygiene practices with all CLC related epidemiological studies. In the meantime, it would be prudent to wash in place of wiping for those who are susceptible to developing CLC from family history or other health reasons.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

I would like to thank, my parents for their support, and for nurturing my curiosity of health sciences. I would also like to thank, Ms. Adrienne White and all laboratory staff at UVic for supervising me in the UVic laboratory. Thanks also goes to the VIRSF Ethics Committee for providing me with permission and guidance to conduct the research. My three anonymous test participants for giving me their time and effort. Last but not least, My Project Advisor Mr. Victor Tymoshuk for his inspiring discussions and his enthusiasm on my work. My gratitude also goes to Arbutus Global Middle School students for participating in the survey, and to the Principal, Mr. Parker for supporting me in the science fair.

REFERENCES

Alexander-Williams J. (1983). Causes and management of anal irritation: (Br Med J (Clin Res Ed). 1983 Nov 19; 287(6404): 1528).

Boyle P. and Langman J. S. (2000). ABC of colorectal cancer Epidemiology: (BMJ 2000;321:0012452): (doi: https://doi.org/10.1136/sbmj.0012452)

Bray F. et. al (2013). Global estimates of cancer prevalence for 27 sites in the adult population in 2008: (Int. J. Cancer: 132,1133–1145 (2013))

Canadian Cancer Society’s Advisory Committee on Cancer Statistics. Canadian Cancer Statistics (2017). Canadian Cancer Society, Toronto, ON: cancer.ca/Canadian-CancerStatistics-2017-EN.pdf . (ISSN 0835-2976).

Chan A. T. and Giovannucci E. L (2010). Primary Prevention of Colorectal Cancer: (Gasteroenterology 2010; 138:2029 –2043). (https://doi.org/10.1053/j.gastro.2010.01.057)

Chen W. et al (2016). Cancer Statistics in China, 2015: (Ca Cancer Journ Clin 2016;66:115–132): (doi:10.3322/caac.21338. Available online at cacancerjournal.com)

Dikshit R., et. al., (2012). Cancer mortality in India: a nationally representative survey: (The Lancet, Volume 379, Issue 9828, Pages 1807-1816)

Fatima A., et. al, (2009). Colorectal Cancer Epidemiology: Incidence, Mortality, Survival, and Risk Factors: (Clin Colon Rectal Surg. 2009 Nov; 22(4): 191–197).

Ferlay et. al (2014). Cancer incidence and mortality worldwide: Sources, methods and major patterns in GLOBOCAN 2012 : (Int. J. Cancer: 136, E359–E386 (2015)) : (https://doi.org/10.1002/ijc.29210).

Forman et.al (2014). Cancer Incidence in Five Continents: (Vol. X. IARC Scientific Publication No. 164. Lyon: International Agency for Research on Cancer).

Kuriki K. and Tajima K. (2006): The Increasing Incidence of Colorectal Cancer and the Preventive Strategy in Japan: (Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2006 Jul-Sep;7(3):495-501).

Marmot et. al. (2007). Food, Nutrition, Physical Activity, and the Prevention of Cancer: a Global Perspective.(URI:http://discovery.ucl.ac.uk/id/eprint/4841).

Mishra et al, (1996). Cancer among American-Samoans: Site-Specific Incidence in California and Hawaii: International Journal of Epidemiology, Vol. 25, No. 4 : (https://doi.org/10.1093/ije/25.4.713).

Moore, M. A. et al (2010). Cancer Epidemiology in the Pacific Islands - Past, Present and Future: (Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2010; 11(0 2): 99–106).

Parkin et. al (1999). Global Cancer Statistics: (CA Cancer J Clin. 1999 Jan-Feb;49(1):33-64, 1).

Pfadenhauer L. M. and Rehfuess E. (2015). Towards Effective and Socio-Culturally Appropriate Sanitation and Hygiene Interventions in the Philippines: A Mixed Method Approach: (Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2015, 12, 1902-1927; doi:10.3390/ijerph120201902).

Rohde H. (2000). Routine Anal Cleansing So-Called Hemorrhoids and Perianal Dermatitis: Cause and Effect? (Dis Colon Rectum April 2000; 561:562).

Stewart B.W. and Wild C. P. (2014). World cancer report 2014: International Agency for Research on Cancer, World Health Organization. (ISBN 978-92-832-0443-5).

Tamakoshi et al, (2017). Characteristics and prognosis of Japanese colorectal cancer patients: (The BioBank Japan Project: Journal of Epidemiology 27 (2017)) : ( https://doi.org/10.1016/j.je.2016.12.004).

World Watch Magazine, July/August (2007). Matters of Scale -Into the Toilet, Volume 20, No.4.

YiU et. al , (2004). Increasing colorectal cancer incidence rates in Japan: (Int. J. Cancer: 109, 777–781) : (https://doi.org/10.1002/ijc.20030). Strategy in Japan: (Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2006 Jul-Sep;7(3):495-501).

Young S. W. et. al (2015). Colorectal cancer incidence in the Aboriginal population of Ontario, 1998 to 2009: (Statistics Canada, Health Reports, Vol. 26, no. 4, pp. 3-9, April 2015).

Websites to get statistics and maps:

http://gco.iarc.fr/today/home

http://www.cancerresearchuk.org/health-professional/cancer-statistics/

worldwide-cancer

(2019, July 22). Worldwide cancer statistics. Retrieved from http://www.cancerresearchuk.org/health-professional/cancer-statistics/worldwide-cancer

For tables and statistics :

http://globocan.iarc.fr/Pages/fact_sheets_cancer.aspx

Cancer today. Retrieved from http://globocan.iarc.fr/Pages/fact_sheets_cancer.aspx

WISHVA KOSGODA

Wishva is currently a Grade 10, student in the Challenge Program at Mount Douglas Secondary School. She is fascinated and inspired by nature and the secrets it holds. Wishva has been competing in science fair since grade 6 (4 years) and has placed first in her category twice. Science and Nature are just two aspects of Wishva’s interests. She is a platinum award winner for both Kumon math and reading programs and has won awards as a piano performer/composer at the Greater Victoria Performing Arts Festival. Her piano compositions are inspired mainly by nature. Wishva also does modern, ballet and contemporary dancing both attached to school and studio. During free time Wishva enjoys writing, reading, dancing, drawing, mastering piano and flute, music composing, exploring nature and cooking. She is also an accomplished field athlete, specialized in throwing events ( Shot Put, Disc and Hammer) and ranked third and fourth at provincials for discus and hammer respectively. She aspires to work in the medical field as an adult and believes her path has yet to be formed.