Davin Martin

Age 13 | Calgary, Alberta

Canada-Wide Science Fair 2019 Excellence Award: Junior Silver Medal | Western University $2,000 Entrance Scholarship

When Dr. Wei-Min Wu of Stanford University pulled a bag of rice from his cupboard and found Indian meal-moths escaping through a hole in the plastic packaging, he thought that the waxworms (larvae) must have eaten through the plastic. Wu and others at Stanford University were intrigued (Jordan, 2015), so they tested the larvae of a similar species, known as Tenebrio molitor (Yang et al., 2015), a type of Darkling Beetle. Their larvae, also called mealworms, were fed expanded polystyrene (Yang et al., 2015), a type of plastic commonly known as Styrofoam. Their experiments focused on the mealworms’ ability to digest the Styrofoam (Yang et al., 2015); however, an effort needs to be made to understand if and how the Styrofoam affects the beetle’s life cycle (Figure 1). Therefore, my experiment aims to examine whether mealworms can live off Styrofoam long enough to reproduce. If so, this is a way to reduce Styrofoam waste from landfills without affecting the offspring of the beetles. Styrofoam waste presently makes up 30% of an average waste facility in the United States (Little, 2018) and is known to be non-biodegradable.

Figure 1. “Mealworm Lifecycle.” Retrieved from Enchanted Learning at https://www.enchantedlearning.com/subjects/insects/beetles/mealworm/mealwormlifecycle.shtml.

PURPOSE & HYPOTHESIS

The purpose of this project is threefold: to show that Styrofoam is a viable food source for the mealworms, to investigate the effects on their lifecycle, and to start the design process for mealworm farming that uses Styrofoam as a food source. It is my prediction that mealworms can live off Styrofoam long enough that they are able to continue their life cycle and reproduce.

PROCEDURE

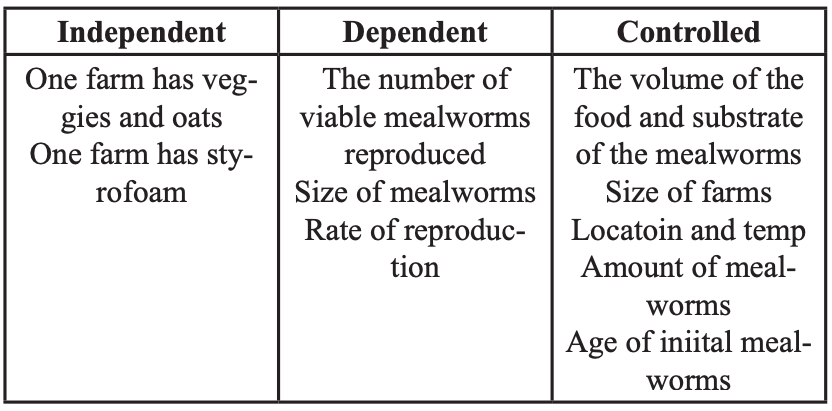

Treatments Two different mealworm farms were built, and the behavior and reproduction rate of the mealworms were compared. In this experiment, the term substrate is used to describe a surface below the mealworms, used for them to grow and feed on (“Mealworms,” n.d.). The control group received oats as a food substrate, while vegetables were used as a water source. The test group received Styrofoam as the food substrate, and water was sprayed once a day. As noted in the introduction, Styrofoam has been proven safe for the mealworms to eat. The experiment was done over 51 days, and my observations were logged in a journal. Since Styrofoam has such a light weight, volume was used instead for a more meaningful representation of the amount. Table 1 describes the variables for this experiment. Farm Construction The farms were based off those from an instructional video created by Mechanical Ninjineer (2016).

Table 1. A description of the variables in this experiment.

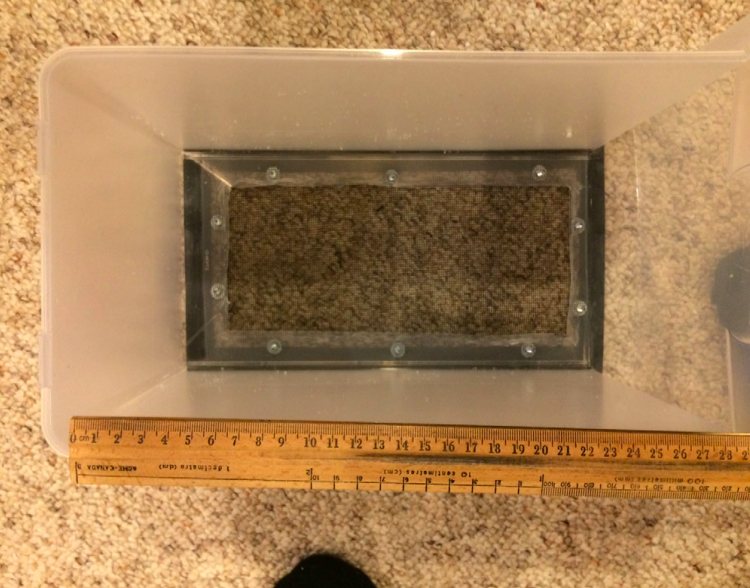

Plastic storage drawers were used for the farms. The first step in building the farms was to cut off the bottoms of the top drawers and replace them with a mesh material (Figure 2) in order for the eggs (the second generation) to fall to the next drawer; this prevents the adults from eating the larvae. Next, the substrates were added to the top drawers (approximately 2518.75 cm3 per farm). Finally, each farm received 250 mealworms. As the experiment progressed, the mealworms from the control group grew bigger, whilst the mealworms from the Styrofoam group remained the same size as when I bought them at two weeks of age. Another observation is that although the mealworms from the Styrofoam group stayed smaller, they progressed into their pupation state faster by six days and grew into adults faster by two days. Hence, the Styrofoam group mealworms reproduced at a rate faster than the mealworms in the oats group.

Figure 2. View of farm drawer with mesh bottom for eggs to fall through.

DISCUSSION

The mealworms in each group were healthy all through the experiment, as demonstrated by their normal eating behaviours and mating behaviours; no behavioural changes were noticed

and both farms had a second generation. In a 51-day period, 250 mealworms ate 1007.5 cm3 of Styrofoam (Table 2), while the estimated yearly amount is 7227.00 cm3 (Table 3).

Table 2. Amount of styrofoam 250 mealworms ate in 51 days.

Table 3. Estimated amount of Styrofoam 250 mealworms can eat in one year. This yearly amount is approximately two large jugs of juice!

Based on my experiment, I have proven that mealworms can use Styrofoam, this non-biodegradable waste, as a sustainable food source for themselves and, moreover, they can reproduce. Since the mealworms from the Styrofoam group were able to reproduce at a faster rate, it means that they were able to get nutrients from the Styrofoam; however, in most cases when a species’ reproduction rate speeds up, it indicates that there is less nutritional value than normal in their food source (Swanson et al., 2016). This then leads to several other items that need to be explored, such as the bioaccumulation of products in the mealworms that eat Styrofoam. This is important to learn about, since mealworms are a food source for poultry, reptiles, as well as humans from various cultures. If mealworms that have fed on Styrofoam are safe to eat, then many industries can benefit from this low-cost food source. Another item that needs further exploration is that since there was an increase in the reproduction rate, there needs to be an investigation of the impact of this on further generations. If the subsequent generations are noted to be less healthy, there is a simple solution to this, which would be to do a crop rotation (Macdonald, 2018). This means having one generation on Styrofoam and the next live off a more nutritious food source such as oats and vegetables, so the nutrition is replenished in the population.

CONCLUSION

This study has shown that mealworms can use Styrofoam as a food substrate and reproduce without any observed behavioural changes. If mealworms can survive off Styrofoam for many generations, then mealworms have the potential to become a valuable tool for many waste facilities. The key is to use the mealworms in the most optimal and safe way. To do this, it must be ensured that their life cycle is able to continue for generations, so the potential consequences of a plastic-based diet should be investigated. As more long-term effects are understood, waste facilities are closer to effectively using mealworms for the decomposition of Styrofoam, which will reduce a significant portion of waste in landfills.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

I would like to thank my father, Robin Martin, who helped me build my farms and finance the project, as well as my mother, Priti Obhrai-Martin, who helped me with applying the scientific method to my project and with understanding animal behaviour. I would also like to thank the Calgary Youth Science Fair for giving me the opportunity to share my project. Finally, I would like to acknowledge Branton Junior High and Mme Dagenais for the opportunity to participate in the Calgary Youth Science Fair.

REFERENCES

Jordan, R. (2015, September 29). Plastic-eating worms may offer solution to mounting waste, Stanford researchers discover. Retrieved from https://news. stanford.edu/2015/09/29/worms-digest-plastics-092915/ Little, M. (2018, October 31). Facts About Landfill & Styrofoam. Retrieved from https://sciencing.com/facts-about-landfill-styrofoam-5176735. html

Macdonald, M. (2018, April 11). Crop rotation. Retrieved from https://www.westcoastseeds.com/blogs/garden-wisdom/crop-rotation Mealworms. (n.d.). Retrieved from http://mealwormcare.org/ Mechanical

Ninijneer. (2016, May 27). How to Build a Mealworm Farm! [Video file]. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vQBrAzr0cmk

Swanson, E., Espeset, A., Mikati, I., Bolduc, I., Kulhanek, R., White, W., … Snell-Rood, E. (2016). Nutrition shapes life-history evolution across species. Proceedings of the Royal Society B, 283(1834), https://doi.org/10.1098/ rspb.2015.2764

Yang, Y., Yang, J., Wu, W., Zhao, J., Song, J., Gao, L., … & Jiang, L. (2015). Biodegradation and mineralization of polystyrene by plastic-eating mealworms: Part 1. chemical and physical characterization and isotopic tests. Environmental Science & Technology, 49(20), 12080-12086. https://doi. org/10.1021/acs.est.5b02661

DAVIN MARTIN

My name is Davin Jacob Obhrai Martin, I am 13 years old and I am from the city of Calgary. Although I was born in Calgary, I spent seven years of my life living in Southeast Asia, where I saw the environmental impact of Styrofoam and other plstics. I then moved back to Canada where I started my science fair projet that investigated mealworms eating styrofoam. I won the Regional Science Fair with a gold medal, and two plaques; one for “BiodiverCity” (awarded by the city of Calgary) and one for winning “Top Junior”. I also received a trophy and the opportunity to participate in the Canada-Wide Science Fair, where I won a silver medal land a scholarship to Western University