WAFAA AMIN & ASIA URQUHART

she/her | age 15 | Halifax, NS

Bronze Medal, Canada-Wide Science Fair

Edited by Natara Ng

INTRODUCTION

Mental health support and resources are poorly distributed and represented in the healthcare system, especially in Canada (The Commonwealth Fund, 2021). Mental illnesses reach 50% of Canadians by age 40 (The Centre for Addiction and Mental Health, n.d.), but the rates of specialized treatment are very low, with 75% of children with mental disorders not having access to specialized treatment services. This rate differs substantially from the 9% of cancer diagnoses that do not receive treatment or some form of supportive care (The Centre for Addiction and Mental Health, n.d.). These differing rates represent a large discrepancy between how we care for those with physical versus mental health conditions. These findings can be tied to high rates of mental illness, lack of healthcare provider time with patients, clinician shortages, and more (Heyhoe et al., 2015). In our project, mental health is broken down into an under-researched and specific topic: Emotions.

Emotions are said to be a phenomenon carrying numerous theories in ancient times and beliefs (Gendron & Barrett, 2009). In ancient Chinese medicine, emotions are narrowed down to five basic feelings that are each associated with a corresponding element and organ in the body: anger with the liver; fear with the kidney; joy with the heart; and sadness and grief with the lung (Vanbuskirk, 2023). Today, there is some general agreement that there are five basic emotions: anger, fear, sadness, disgust, and enjoyment. In this study, we focus on negative-valence emotions (NVE), which encompass feelings characterized by a negative emotional tone. One well-researched physiological response to emotions is stress, particularly the fight-or-flight response. The fight-or-flight response is a physiological reaction that occurs in response to a perceived harmful event, attack, or threat to survival (Jaremka et al., 2011). The sympathetic nervous system is a branch of the autonomic nervous system (ANS) that triggers the fight-or-flight response, providing the body with higher energy and arousal so that it can respond to perceived dangers (Chawla & Guest, 2016). While stress as a physiological response has deep-researched roots, there are many different emotions that patients engage with in healthcare. However, there is little representation of these emotions in healthcare and the role they play in patient care (Heyhoe et al., 2015). Acknowledging and addressing this gap in research may be vital for improving the quality of care provided to individuals experiencing various emotional states (Edgman-Levitan S, n.d). Therefore, this study aims to explore the nuanced emotional experiences of patients, focusing not only on stress but also on other NVEs, to shed light on their impact on care and potential interventions in healthcare settings. Specifically, we aim to discern the relationships between NVEs and 1) social determinants of health (SDH), 2) physiological responses, and 3) patient-centered emotional care in pediatric healthcare settings.

METHODS

Objective 1

Our first objective was to identify relationships and trends between negative-valence emotions and SDH in pediatric populations. The researchers created an anonymous online survey through Google Forms. The survey was distributed to a spectrum of pediatric populations through posters containing a QR code, social media distribution, and through the school community. The survey received 119 respondents, and data were analyzed using Microsoft Excel. The survey contained 14 questions that aimed to collect information regarding SDH and other socio-demographic factors such as age and region. Information about principal SDH such as gender, ethnicity, and religion were collected. Participants also provided information about their emotional experiences and reactions to these experiences.

To assess the relationship between SDH and emotional experiences of respondents, we used Google Excel for a comprehensive analysis. Our approach involved looking at the data to discern patterns and determine the likelihood of specific emotions occurring within various SDH contexts. We identified noteworthy occurrences ("must-see") and potential associations ("might potentially see") for each emotion, contributing to a thorough understanding of the relationships between emotions and SDH.

Objective 2

Our second objective was to explore healthcare professionals' perspectives on emotional care in pediatric healthcare and the representation of emotional distress in hospital settings. A questionnaire in an interview setting and discussion plan were developed, consisting of six open-ended questions. One healthcare professional, a cancer researcher, and another, a cardiothoracic surgeon, participated in an in-person and online questionnaire via an interview. The data obtained from the questionnaire and interview was synthesized in Google spreadsheets and Google Documents.

Objective 3

In our third objective, we investigated relationships between changes in vital signs and observed reactions with the five most prevalent NVEs: loneliness, guilt, failure, stress, and emptiness (Chawla & Gest, 2016). Our aim was to identify trends in physiological arousal associated with these specific emotions and contribute insights into the physiological manifestations of emotional experiences.

The researchers conducted an emotion-induction study in collaboration with Gorsebrook Junior High School. Six pediatric patients participated in a controlled setting where emotional stimuli were presentedpresented, and physiological responses were measured with the aid of body maps (Nummenmaa et al., 2013). Ethics approval was received prior to the study and all participants signed consent forms. Physiological measurements included variables such as temperature, heart rate, and more, forming the basis for the application of a novel formula to express the relationship between physiological arousal and emotional state, ΔAR = f(ΔEM), where ΔAR is the change in physiological arousal and ΔEM is the change in emotional state. This innovative approach aligns with our broader exploration of emotions in pediatric healthcare settings.

RESULTS

Objective 1

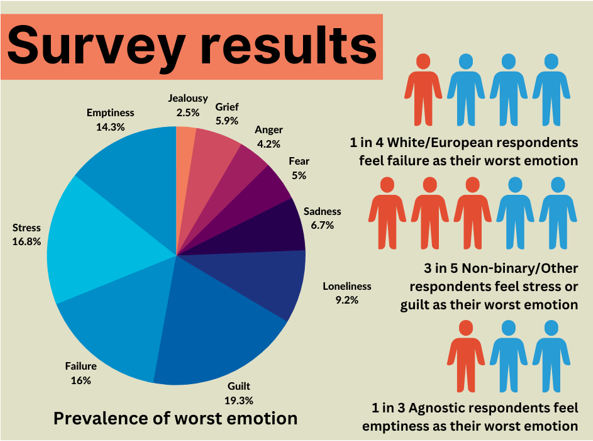

Guilt emerged as the most prevalent negative-valence emotion, chosen by 19.3% of respondents as their worst emotion. Stress, failure, emptiness, and loneliness followed in decreasing order (Figure 1). Ethnicity, gender, and religion showed significant relationships with participants' choice of worst emotion. The findings suggest that specific SDH such as ethnicity and gender have substantial implications for how pediatric patients perceive and experience emotions. For instance, White/European respondents showed a higher tendency to choose failure as their worst emotion. Asian respondents, on the other hand, more frequently selected loneliness and sadness.

The complex interplay between gender identity and emotion choice was also evident, with boys frequently identifying failure and girls associating with guilt. Non-binary/other respondents leaned towards stress as their worst emotion. Furthermore, distinct emotional responses were linked to religious affiliations, with agnostic respondents often associating their worst emotion with emptiness. Interestingly, girls and boys displayed divergent reactions to low-arousal emotions. Girls often mentioned crying as a response, while boys referred to coping mechanisms like going to the gym.

Objective 2

Healthcare professionals emphasized the lack of emotional recognition within hospital settings, reflecting on the challenges of addressing emotional and psychological symptoms compared to physical symptoms. Both shared the sentiment that healthcare providers find it easier to discuss and treat physical ailments rather than delve into the emotional aspects of patients' experiences. (Urquhart & Desokyey, 2023).

The professionals' shared perspectives led to a unanimous call for patient-centered care as a mechanism to bridge the gap between emotional and physical wellbeing. Building stronger doctor-patient relationships, providing timely diagnosis, implementing evidence-based care, and interdisciplinary collaboration were underscored as essential components to better address patients' emotional health. Establishing these practices, the healthcare providers argued, would contribute to more accurate treatment, enhanced patient quality of life, and a holistic approach to healthcare delivery (Urquhart & Desokyey, 2023)

Objective 3

After the study in the controlled setting where emotional stimuli were presented, the results were analyzed. Graphs were generated to visually represent the complex interactions observed (Figure 2). Emotions elicited distinct physiological reactions, indicating the potential influence of emotions on the body's responses.

The relationship between emotions and vital signs revealed intriguing patterns. Guilt, for instance, consistently increased heart rate while reducing axillary temperature. Stress induced rapid fluctuations in pulse pressure and elevated body temperature, indicating an intense physiological response. Additionally, observed reactions, such as flushness, movement, and talk, showed consistent synchronization with vital sign changes during emotion-inducing activities.

High or low arousal states were triggered depending on emotion. Stress, a high arousal emotion, resulted in heightened mean values in all vital signs and observed responses compared to baseline. Loneliness resulted in lower mean values in 4 out of 6 vital signs and observed reactions. Failure, guilt, and emptiness lay on the arousal spectrum between stress and loneliness. During exposure to guilt stimuli, heart rate (bpm) was above baseline 100% of the time (mean of +10 bpm increase) whereas axillary temperature decreased an average of 0.46 degree Celsius. Exposure to stressful stimuli resulted in enormous spikes and dips in pulse pressure, as well as an average increase of 0.54 degree Celsius in body temperature, suggesting large fluctuations and physiological responses in the body to this emotion (Figure 3). Relationships existed across physiological responses. For example, when respiratory rate increased or decreased, blood pressure followed suit 90% of the time. Furthermore, all observed reactions either increased (higher aroused) or decreased (lower aroused) at the same pace 74.3% of the time, i.e. stress increased flushness, movement, and talk. For observed reactions, stimuli that invoked feelings of failure, guilt, and stress elevated flushness, while those that invoked emptiness and loneliness led to a decrease in flushness. Across participants, stress, loneliness, and emptiness showed consistent increases and decreases with both vital signs and observed reactions. Guilt and failure were more variable across participants, suggesting more individualized responses to these emotions. Some emotions may be more internalized than others and may have a unique dependance on personal history with that emotion.

Developing the formula ΔAR = f(ΔEM)

The formula was derived based on the findings from Objective 3 of the study, which explored the physiological responses associated with different emotional stimuli. By analyzing the data collected during the study, we observed patterns in how emotions influenced physiological arousal levels. This formula expresses the relationship between the two variables and maps changes in emotion to changes in arousal. To determine the function f that maps changes in emotion to changes in arousal, statistical analysis such as linear regression or correlation analysis can be used. The strength of the relationship between emotions and physiological arousal can be determined using the magnitude of the correlation coefficient. A positive correlation coefficient indicates that as emotional arousal increases, physiological arousal also increases, while a negative correlation coefficient indicates an inverse relationship between emotional and physiological arousal. This calculation method and formula can be used to study the relationship between emotions and physiological arousal in a specific individual or population.

DISCUSSION

This study provides insight into the social, physical and physiological relationships with emotions. For the survey exploring relationships between NVEs and SDH, the various emotional experiences among diverse demographic groups sheds light on the interplay between culture, gender, and emotions. White/European respondents, for instance, exhibited a higher tendency to choose failure as their worst emotion, hinting at potential cultural influences on emotional experiences. Moreover, non-binary/other respondents leaned towards stress, emphasizing the need to further investigate the emotional experiences of individuals outside traditional gender binaries. The results of the interviews and the emotion-induction study show that a person's symptoms and conditions could be worsened by emotional physiology, potentially making accurate diagnoses challenging. If providers are spending all their time, resources, and treatment towards physical illnesses, it will be impossible to alleviate distressing symptoms because of the large role that emotions play in pediatric health, especially when heightened by hospital settings.

Patient-Centered Emotional Screening Tool (PCEST)

A hallmark of this research is the creation of the Patient-Centered Emotional Screening Tool (PCEST). PCEST offers a revolutionary approach to address the emotional wellbeing of pediatric patients within healthcare settings. Every patient presumably experiences emotions, some of which are acute, with a progression too distressing and unmanageable. These emotions are either hospital-induced or from outside factors. With a PCEST, patients have the opportunity to improve hospital stays, experience, and treatment success, and achieve an overall better quality of life. By incorporating insights from ANS functions and the novel formula, ΔAR = f(ΔEM), PCEST has the potential to not only quantify emotions but also predict physiological responses using vital signs, enhancing quality of care by integrating emotional considerations into patient management strategies. PCEST could be implemented with low cost and patient-instigation, meaning a clinician would not have to lead the screen themselves. PCEST is patient-centered, meaning the patient can follow their journey on their own management, time, and pace. It is shown that this patient-centered transition leads to less dehumanization in healthcare settings and creates a more trusting patient- provider relationship (Edgman-Levitan & Schoenbaum, 2021).

ANS Theory and Future Potential

There is little research on negative-valence emotions and low/high arousal regarding in relation to their effect on the limbic system and mainly the ANS. The results of our study suggest that many high arousal emotions can have similar effects as the fight-or-flight response in the sympathetic nervous system, while low arousal emotions may stimulate parasympathetic nervous system pathways. Emotions and their levels of arousal and valence suggest impact on bodily responses, such as heart rate, blood pressure, respiration, digestion, and sexual arousal, and eventually help us understand more concretely how chronic or highly distressing emotions can affect your body This means that severe responses to emotions can be predicted by mapping out the physiological functions of the autonomic nervous system (Figure 5). With this novel approach to emotions, healthcare providers and researchers can predict the response if, for example, guilt is felt at an intensity of 8/10 (which would be in between the two spectrums), and maintain patient health in the physiological responses that we know are connected to the ANS.

FUTURE DIRECTIONS

While this study provides valuable insights into the physiological responses associated with emotions, the exploration of physiological connections can be further expanded. Future research can go into other physiological markers beyond heart rate, blood pressure, and temperature. Heart rate variability, for instance, offers a nuanced perspective on the autonomic nervous system's modulation and could shed light on the dynamic interplay between emotions and physiological responses. Exploring exocrine and endocrine functions may uncover additional physiological pathways that emotions influence, offering a more comprehensive understanding of emotional impacts on health.

The Patient-Centered Emotional Screening Tool (PCEST) also introduces a promising avenue for enhancing emotional care within pediatric healthcare. Collaboration with healthcare professionals is essential to fine-tune the tool and ensure its alignment with evidence-based treatment and coping strategies. By actively involving healthcare providers, patients, and researchers, PCEST's impact can be maximized, addressing patients' emotional health needs during their hospital stays. As PCEST evolves, integrating it into real-world healthcare settings presents an opportunity to assess its effectiveness and make necessary improvements to ensure that it remains relevant and responsive to the changing needs of pediatric patients.

Expanding the Formula ΔAR = f(ΔEM)

The novel formula ΔAR = f(ΔEM), introduced to quantify emotions and predict physiological responses, holds substantial potential for further development. By refining and expanding this formula, researchers can achieve a more accurate representation of arousal rates during emotional distress. The formula's expansion could include incorporating additional variables that influence emotional experiences, such as personal history, social context, and cognitive responses. Collaborations between researchers specializing in psychology, physiology, and data science could lead to a comprehensive model that captures the intricate relationships between emotions and physiological reactions.

CONCLUSION

In summation, this research advances the movement towards comprehensive emotional care in pediatric healthcare. The holistic approach presented in this paper, encompassing social determinants, healthcare provider perspectives, physiological responses, and the pioneering PCEST offers a pathway to better patient experiences, outcomes, and well-being. As the realms of emotional care and physiological understanding intertwine, the potential to revolutionize pediatric healthcare is within reach. This research marks not only a step forward in understanding emotions' impact on health but also a call to action to reshape the landscape of pediatric healthcare, making it more empathetic, holistic, and responsive to patients' emotional well-being.

The basic version of the PCEST guide can be found here:

https://www.canva.com/design/DAFh6Wz1j_w/UR7edJNuucI8xIrMldoS-w/edit?utm_content=D AFh6Wz1j_w&utm_campaign=designshare&utm_medium=link2&utm_source=sharebutton

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

We would like to thank the IWK Health Center in Halifax for their help and inspiration for developing this research project. Last year, we were both diagnosed with illnesses and underwent hospital stays and treatment in a prominent pediatric hospital in Halifax, the IWK. During our stays, we noticed a recurring theme: the primary focus on physical treatment and care. This is due to physician time with patients, under-staffing, lack of evidence-based research on emotions, and more. However, this resulted in less trust and opportunity to talk about mental and emotional health with healthcare providers. Being there for both physical and psychiatric illnesses, there were lots of emotions that arose, both due to the hospital setting and external factors. We felt as though our emotions greatly impacted our physiology and social lives. In addition, we are both interested in becoming physicians or healthcare providers in the future, but still felt some reluctance and timidness at the thought of countless physical interventions (e.g., vitals, treatments). This made us wonder about the impact of a lack of emotional care on pediatric patients because hospital settings can be extremely negatively emotion-inducing. Emotions, to say the least, are under-represented, mis-conceptualized, and lack evidence-based research in healthcare. Do emotions worsen a patient's quality of life, and if so, why are they vastly under-researched compared to other physical illnesses?

In addition to our personal experience, so many people helped along the way in generating and aiding this project. A huge thanks goes to Sonja Goold, our science teacher, for letting us experience this amazing opportunity. We want to thank Gorsebrook Jr. High for helping us throughout the process of finding time and resources. Thank you to Ms. Andrews for letting us use her cozy, welcoming room for our experiment. Your generosity and hospitality have made our project comfortable for everyone. We are also immensely grateful to Omneya Desokyey and Glorija Bowman for their wise advice and supervision during our experiment. Special thanks to Robin Urquhart for sharing her knowledge of statistical analysis and research, her professional insights were extraordinary. We most importantly want to give our deepest thanks to all the participants who volunteered their time. Your participation was absolutely essential. This research wouldn’t have existed without you all. Finally, thank you to the HSTE committee and people at CWSF for making dreams possible.

REFERENCES

The Centre for Addiction and Mental Health. (n.d.). Mental Illness and Addiction: Facts and Statistics. CAMH. Retrieved October 1, 2023, from https://www.camh.ca/en/driving-change/the-crisis-is-real/mental-health-statistics

Chawla, J., & Gest, T. R. (2016, June 28). Autonomic Nervous System Anatomy: Overview, Gross Anatomy, Cardiac and Vascular Regulation. Medscape Reference. Retrieved April 30, 2023, from https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/1922943-overview

Edgman-Levitan S, Schoenbaum SC. Patient-centered care: achieving higher quality by designing care through the patient's eyes. (2021). Israel Journal of Health Policy Research 10(1): 21. doi: 10.1186/s13584-021-00459-9.

Gendron M, Barrett LF. (2009). Reconstructing the past: A century of ideas about emotion in psychology. Emotion Review 1(4): 316-339. doi: 10.1177/1754073909338877

Heyhoe, J., Manning, P., & Maguire, L. (2015, December 18). The role of emotion in patient safety: Are we brave enough to scratch beneath the surface? NCBI. Retrieved October 1, 2023, from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4793767/

Jaremka, L. M., Gabriel, S., & Carvallo, M. (2011). What makes us feel the best also makes us feel the worst: The emotional impact of independent and interdependent experiences. Self and Identity, 10(1), 44-63. https://doi.org/10.1080/15298860903513881

Nummenmaa, L., Glerean, E., Hari, R., Hietanen, J. K. (2013). Bodily maps of emotions. Psychological and Cognitive Sciences, 111(2), 646-651. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1321664111.

The Commonwealth Fund. (2021, August 4). Mirror, Mirror 2021: Reflecting Poorly. Commonwealth Fund. Retrieved December 8, 2023, from https://www.commonwealthfund.org/publications/fund-reports/2021/aug/mirror-mirror-2021-reflecting-poorly

Urquhart, R., & Desokyey, O. (2023, February 28). Healthcare professionals' thoughts on the treatment of emotions in the system [Personal].

Vanbuskirk, S. (2023, January 10). How Emotions and Organs Are Connected in Chinese Medicine. Verywell Mind. Retrieved December 8, 2023, from https://www.verywellmind.com/emotions-in-traditional-chinese-medicine-88196

FIGURES

Figure 1: Emotional Responses and Sociodemographic Influences | Guilt emerged as the most prevalent negative-valence emotion among pediatric patients, influenced by factors such as ethnicity, gender, and religion. The findings underscore the importance of tailored emotional care approaches in healthcare settings.

Figure 2: Heart Rate Variations Across Emotional Responses | The measurements of heart rate (HR) for each emotion by participant, with indication of HR over baseline (green), and HR under baseline (red). Guilt exhibits a consistent rise in heart rate amidst varied vitals and observed reactions, indicating distinctive sympathetic nervous system activation possibly involving heightened catecholamine release compared to typical stress-induced fight-or-flight responses.

Figure 3: Patterns of Arousal Levels from Observed Reactions | Arousal levels, measured on a -4 to +4 scale for observed reactions (flushness, movement, talk). Flushness findings show stress, failure, guilt increase it, while emptiness, loneliness decrease it. Movement and talk indicate emptiness as low-arousal, stress as high. Stress, emptiness, loneliness show consistent trends; guilt, failure are more variable.

Figure 4: Emotional Spectrum and Correlation with Physiological Responses | Spectrum of low to high arousal, illustrating the emotional placement. Illustrating the correlation amongst the vitals and observed reactions. These findings suggest trends in emotional reaction and the possibility of steady treatment in emotional care.

Figure 5: Correlation of Vitals and Observed Reactions on the Arousal Spectrum | Arousal spectrum, illustrating the correlation amongst between the vitals and observed reactions. These findings suggest trends in emotional reaction and the possibility of steady treatment in emotional care.

ABOUT THE AUTHORS

Wafaa Amin

Wafaa is currently a grade 10 student attending Citadel High School in Halifax, Nova Scotia. She’s a very curious person and love questioning everything. She is a enthusiastic first aid provider and teacher who works as a part-time swim instructor. Wafaa is additionally bilingual in both French and English, having won awards for her French proficiency. Her first steps into the love off all thing STEM was thanks to her beloved parents, and of course her working body. By always questioning her difficult situations, not in terms of why she’s in that situation, but rather how she could prevent others from experiencing the same pain or discomfort—she’s always motivated to make a lasting impact on the health world.